Breathing and Internal Mechanics in Chen-Style Taijiquan

A technical reflection summing up Zhang Maozhen’s writings

For my exploration of breathing practice in Chen-Style Taijiquan, see the article Breathing Methods in Chen Taijiquan . As probably you have seen, I like to "triangulate" the topics in our lineage by comparing different students of Chen Zhaokui. Here I try to sum up Zhang Maozhens thoughts, from his book “The Essence of Chen-Style Taijiquan”:

In Chen-Style Taijiquan, breathing is not an isolated breathing technique but part of a larger system integrating movement, structure, and intention. In his discussion of Taijiquan breathing, Chen-style practitioner and author Zhang Maozhen (张茂珍) emphasizes that the development of breathing must follow the gradual maturation of the practitioner’s skill rather than being imposed artificially from the beginning.

At the early stages of practice, the primary task is learning the form and establishing correct body mechanics. During this stage, breathing should remain natural. The classical Chen-style approach does not begin with complicated breathing exercises but allows the practitioner to develop familiarity with the movements first. Only once the choreography of the form becomes more stable does breathing begin to consciously coordinate with the opening and closing dynamics of the movements.

Zhang describes a progressive training process consisting of several stages. Initially, breathing remains completely natural. In the next stage, breathing and movement begin to coordinate. A simple guideline sometimes used during this phase is that lifting movements correspond to inhalation, while lowering movements correspond to exhalation. However, these associations should not be interpreted as rigid rules; they function mainly as temporary training aids.

As practice deepens, the practitioner gradually shifts attention. One stage emphasizes awareness of inhalation while allowing exhalation to occur naturally, while another reverses this focus. Eventually, breathing again becomes natural and unforced, but now it is integrated into the whole-body movement of Taijiquan. In other words, the final stage returns to natural breathing, though at a much deeper level of internal integration.

Within Chen-style Taijiquan, breathing is generally understood as abdominal breathing (腹式呼吸). The classical qualities of proper breathing are often summarized as being deep (深), long (长), fine (细), even (匀), slow (缓), and soft (柔). These qualities support relaxation and internal continuity. At the same time, Zhang stresses that breathing should never become artificially slow or forced. Excessively slow breathing may lead to stagnation in the body’s internal dynamics and produce rigidity rather than fluidity.

A classical principle frequently cited in Taijiquan literature captures this idea succinctly:

在气则滞,在意则活

“If one relies on qi, there will be stagnation; if one relies on intention, there will be liveliness.”

In practical terms, this means that the practitioner should not attempt to manipulate breathing directly through muscular effort. Instead, breathing should follow the intention (yi 意) and the structure of the body.

Several traditional concepts describe how breathing interacts with internal body mechanics. One of the most central is 气沉丹田 (qi chen dantian), often translated as “qi sinks to the dantian.” In practice, this does not mean forcefully pushing the abdomen outward or compressing the lower belly. Rather, it refers to allowing the breath and awareness to settle naturally into the lower abdominal region while maintaining an upright posture, an open chest, and relaxed shoulders.

Another important concept is 气宜鼓荡 (qi yi gudang), which describes a pulsating or oscillating movement of internal energy within the abdomen. Through the natural movement of the diaphragm during abdominal breathing, the pressure within the abdominal cavity changes rhythmically. This produces a subtle sense of expansion and contraction that supports the circulation of internal force.

The text also refers to 出肾入肾 (chu shen ru shen), literally “exiting the kidneys and entering the kidneys.” This phrase describes the role of the waist and lower back in transmitting movement through the body. In Chen-style mechanics, rotational movement of the waist acts as a central driver of force. The torso and ribs expand and contract dynamically in response to this rotational movement, sometimes described metaphorically as opening and closing like fish gills.

When these internal relationships become more integrated, the practitioner may experience the state described as 气遍周身 (qi bian zhoushen), meaning that qi permeates the entire body. In practical terms, this refers to a coordinated state in which breathing, movement, and structural alignment operate as a unified system.

Alongside these breathing principles, Zhang also highlights several mental and structural qualities that support proper internal organization. One well-known principle is 虚领顶劲 (xu ling ding jin), often translated as “lightly lifting the crown.” This instruction encourages a subtle upward extension through the crown of the head while allowing the neck to remain relaxed and free of tension.

Other concepts such as 胸口纳气 (xiongkou naqi), gathering the breath in the chest area, and 皮毛要攻 (pimao yao gong), activating the skin and hair, describe increasingly subtle stages of internal awareness in which breathing, posture, and the body’s surface sensations become interconnected.

Ultimately, the purpose of these methods is not to produce specialized breathing techniques but to cultivate a state in which movement, breathing, and intention operate together naturally. Classical Taijiquan theory describes this final condition as:

表里一致,形神兼备

“Internal and external become unified; form and spirit are both complete.”

In this sense, breathing practice in Chen-Style Taijiquan is less about controlling the breath and more about allowing breathing to emerge naturally from correct structure, relaxed movement, and focused intention.

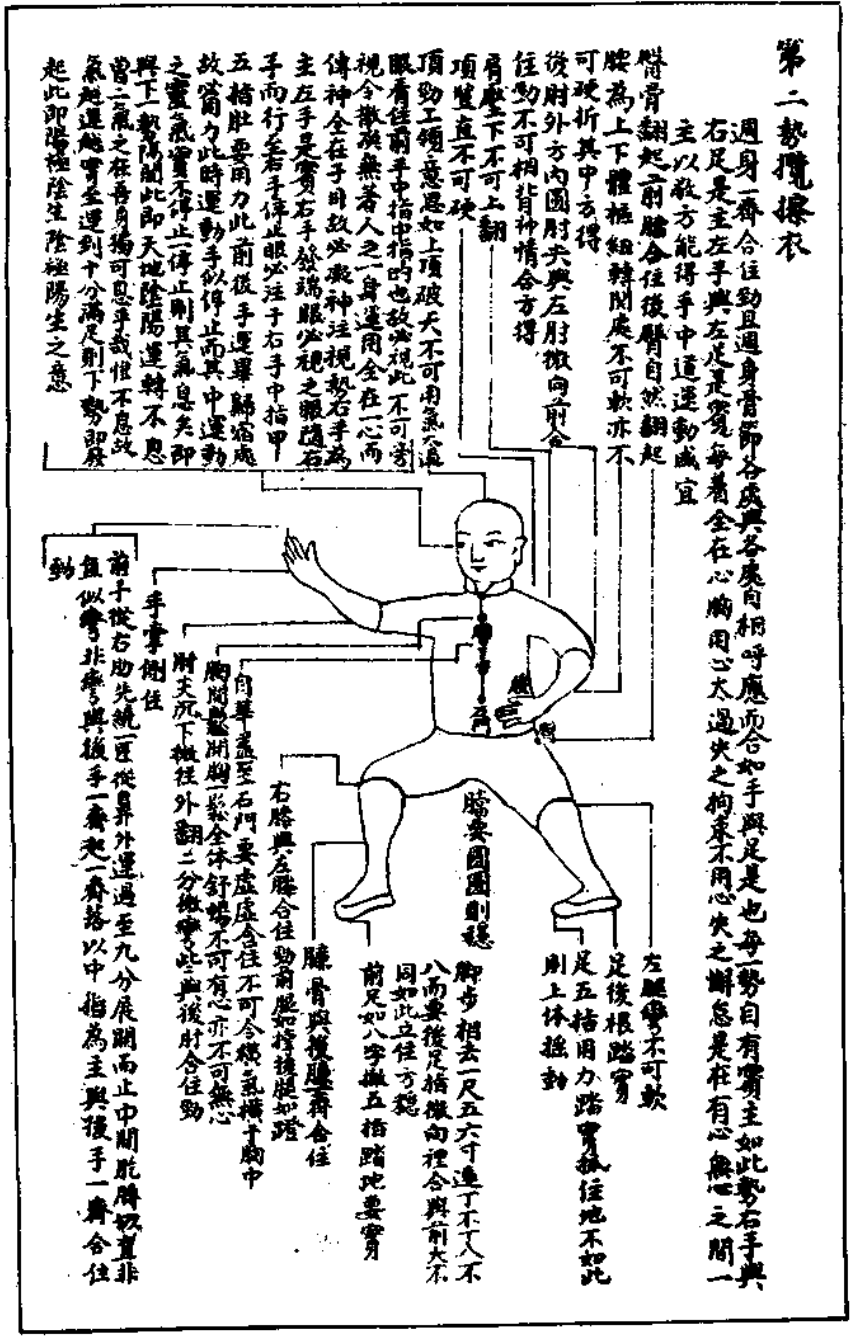

When we start with a practice like Taijiquan, I think next to training the art we will always have a lot of learning (1) to do. Learning comprises stuff like learning movements, learning patterns, drills, learning names for movements, learning concepts (like in the image on the left from Chen Xin about the requirements of a certain posture) and some theory which we need to be able to practice well. After a while the learning aspect may subside a bit so the training (2) aspect can increase and become our main focus. Training then means drilling movements and movement patterns by using the specific concepts we learned.

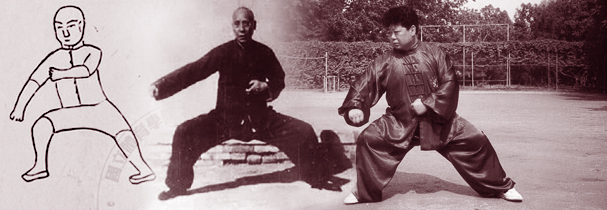

When we start with a practice like Taijiquan, I think next to training the art we will always have a lot of learning (1) to do. Learning comprises stuff like learning movements, learning patterns, drills, learning names for movements, learning concepts (like in the image on the left from Chen Xin about the requirements of a certain posture) and some theory which we need to be able to practice well. After a while the learning aspect may subside a bit so the training (2) aspect can increase and become our main focus. Training then means drilling movements and movement patterns by using the specific concepts we learned.  Chen Zhaokui (January 24, 1928 - May 7, 1981), ancestral home in Chenjiagou, Wenxian County, Henan Province, settled in Beijing with his father. He is the representative of the eighteenth generation of the Chen family, and is known as "High Divine Fist" 神拳太保.

Chen Zhaokui (January 24, 1928 - May 7, 1981), ancestral home in Chenjiagou, Wenxian County, Henan Province, settled in Beijing with his father. He is the representative of the eighteenth generation of the Chen family, and is known as "High Divine Fist" 神拳太保.

Summary: This is about communication and miscommunication when teaching Taijiquan or writing about (internal) martial arts. Also how language and concepts (proverbs and such) shape our practice, how we can relate to that while learning or teaching the arts and how to separate, connect and integrate your body experience and hone skills.

Summary: This is about communication and miscommunication when teaching Taijiquan or writing about (internal) martial arts. Also how language and concepts (proverbs and such) shape our practice, how we can relate to that while learning or teaching the arts and how to separate, connect and integrate your body experience and hone skills.